26. Postcards from Texas

Within the shape of fragments

we were entertained within

rooms of imported mahogany

and rich red fire according

to the ancient usage of the north.

A music wandered like a breath,

and we slept in the soft security

of the melody of the bagpipe

playing against our dreams.

We learned, as people away

from home are apt to learn,

that everything has its history,

even in fragments, even in

pieces small enough to remember,

and, as we slept, as we dreamt,

as we awakened and listened to

what the elderly gentleman said,

we learned that this was the tune

that the piper played while they

were burning. And he knocked

the ashes out of his tobacco pipe.

Ashes and thrashes, thrashes

then ashes, we all turn to dust

as it all burns away before us:

wallpaper, carpeting, furniture,

wood, flesh, eyes, and teeth.

You might well ask yourself

how sane is a philatelist?

and you would be right to do so.

Slips of perforated paper

torn into squares, licked and stuck

to paper and sent away, they are

the adventurers of the world,

those incapable of not moving.

Under the philatelist’s feet

there spreads a green growth

of soft ferny carpeting

with thin green twines growing

up the legs of the chair where

the philatelist sits, eye against

magnifying glass so he can see

a world too small eyes.

He had been, as I have, out

in Africa for three years, and what

he remembers most are leeches

and termites in sickening profusion

and the illustrations on his stamps.

The jungle is burdened by heat

and throbbing with life, so they ate

the first Bishop of Bahia, two Canons,

the Procurator of the Royal Portuguese

Treasury, two pregnant women,

and several children. The buttocks

provided the best meat, yet they

did not have the advantage of

a philatelist. In the jungle, everything

eaten grows large enough to eat,

everything foreign has an air

of the exotic, and that they gave

as the reason for eating the delicate

little children, tasty as they were.

Our life was a pure Augustan

splendour, as we would read

the languid novels of Swift,

the paltry poetry of Pope.

The world was rich with words,

but beyond the triple entrance

there spread a hexagonal forecourt,

as if an edifice to war. The figure

of Poetry stood flanked by bulls,

his figure worn but his identity sure,

crowned in the fanned-out calathos,

his arms exclamatory around his body,

quartered with faces of lesser gods,

those of the Novel or Essay or

the Clerihew. With a rich ale

in hand and a pewter flagon,

we would read their worldly words

for the leisure of our days or nights.

We once were students,

and retained a memory,

a relic actually, of those

sanguine days when we

had used to lie awake

night after night with a book

of poetry under the pillow,

hoping for an inspiration

from words that came to us,

though only from a page.

The severed heads of worthies

decorated the western gates

of the city. They were fragments

of people but complete in their

own way. We knew who they were.

we were entertained within

rooms of imported mahogany

and rich red fire according

to the ancient usage of the north.

A music wandered like a breath,

and we slept in the soft security

of the melody of the bagpipe

playing against our dreams.

We learned, as people away

from home are apt to learn,

that everything has its history,

even in fragments, even in

pieces small enough to remember,

and, as we slept, as we dreamt,

as we awakened and listened to

what the elderly gentleman said,

we learned that this was the tune

that the piper played while they

were burning. And he knocked

the ashes out of his tobacco pipe.

Ashes and thrashes, thrashes

then ashes, we all turn to dust

as it all burns away before us:

wallpaper, carpeting, furniture,

wood, flesh, eyes, and teeth.

You might well ask yourself

how sane is a philatelist?

and you would be right to do so.

Slips of perforated paper

torn into squares, licked and stuck

to paper and sent away, they are

the adventurers of the world,

those incapable of not moving.

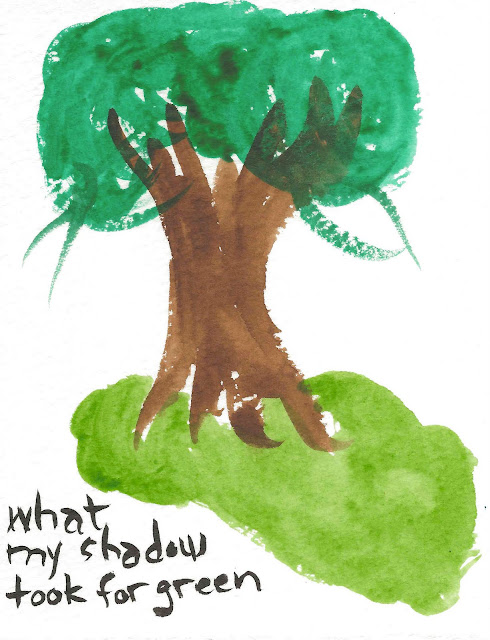

Under the philatelist’s feet

there spreads a green growth

of soft ferny carpeting

with thin green twines growing

up the legs of the chair where

the philatelist sits, eye against

magnifying glass so he can see

a world too small eyes.

He had been, as I have, out

in Africa for three years, and what

he remembers most are leeches

and termites in sickening profusion

and the illustrations on his stamps.

The jungle is burdened by heat

and throbbing with life, so they ate

the first Bishop of Bahia, two Canons,

the Procurator of the Royal Portuguese

Treasury, two pregnant women,

and several children. The buttocks

provided the best meat, yet they

did not have the advantage of

a philatelist. In the jungle, everything

eaten grows large enough to eat,

everything foreign has an air

of the exotic, and that they gave

as the reason for eating the delicate

little children, tasty as they were.

Our life was a pure Augustan

splendour, as we would read

the languid novels of Swift,

the paltry poetry of Pope.

The world was rich with words,

but beyond the triple entrance

there spread a hexagonal forecourt,

as if an edifice to war. The figure

of Poetry stood flanked by bulls,

his figure worn but his identity sure,

crowned in the fanned-out calathos,

his arms exclamatory around his body,

quartered with faces of lesser gods,

those of the Novel or Essay or

the Clerihew. With a rich ale

in hand and a pewter flagon,

we would read their worldly words

for the leisure of our days or nights.

We once were students,

and retained a memory,

a relic actually, of those

sanguine days when we

had used to lie awake

night after night with a book

of poetry under the pillow,

hoping for an inspiration

from words that came to us,

though only from a page.

The severed heads of worthies

decorated the western gates

of the city. They were fragments

of people but complete in their

own way. We knew who they were.

Comments

Post a Comment