19. The Voice that Needs No Echo to Sound

I wonder what the cold is. It seems to be one

of the three states of the same substance:

cold, wet, dark—the interlocking symptoms

of drowning. Our three dogs press into

the night, unaware of cold, impervious to darkness,

even the old blind one, which ventures deep

enough to disappear into the night. The colors

of the night are black for night and white

for anything that we can see within it. In

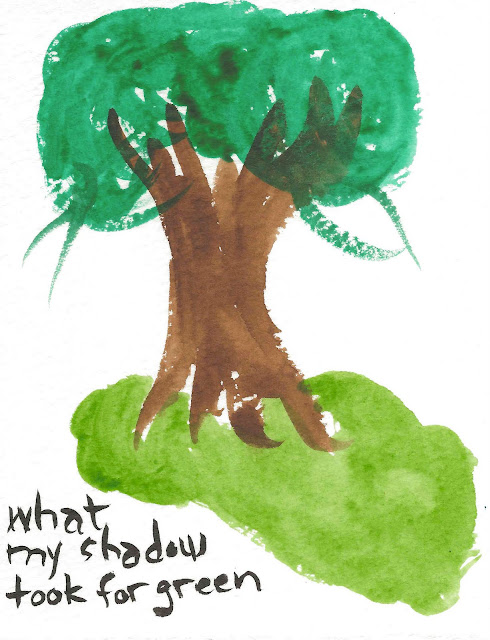

daylight, green dominates and everything

grows into its size. What is small yet infinite

at night is large yet finite during the day. Plants

surround us, prepared to conquer the world.

Maybe not in Arizona, though, which is

a different world created out of different

colors and substances. You have the same night

we have, but your day differs from ours, just

as we might share dreams but our lives differ. Lives,

as instances of daylight, always differ.

I wonder if words work the same way, if

the usual way we speak resembles

night, something that envelops us but

isn’t us. There are also the ways we use

words for ourselves, not so much

to communicate but to be, how you

visually twist a body of text until it is

something else, a contortionist of

words, a measure of your eye,

a means of not speaking, the way you

choose to not write, the stripping

of sense from every word, so that the

chitinous shell of the word remains,

empty but glistening and empty.

My mother-in-law continued to talk tonight

even after going to bed. She asked many times

what had made that last noise she had heard.

She said goodnight to the darkness, and repeated

that goodnight. She repeated the phrases she had

said many times during the day, phrases

that had lost their meaning except that they kept

her safe. The words meant nothing anymore,

but they protected her. If she had those words, if

she could only speak them, she knew she was safe.

This afternoon, I pulled out my inks,

a walnut ink of wavering browns and

India ink, which is always nothing but black,

and I drew letters and words with them,

but ones that didn’t exist, ones that existed

only as I willed them to be. While I worked,

spreading ink over pieces of white paper,

my mother-in-law kept asking me what

I was doing, and every time I said,

“I’m writing,” because writing is the process

of making words appear on a page, anything

we’ve made and seen can be a word to us.

It is too late for writing, too late for words.

Even this close to summer, the Adirondacks

hold their cold, and I need a warm sleep.

I should stop writing now, because I don’t have

the ability to write anymore, I cannot

write it right, and everything leans heavily

into sleep. I am reduced to a human weight. If I fall,

I could drown in the darkness surrounding us.

of the three states of the same substance:

cold, wet, dark—the interlocking symptoms

of drowning. Our three dogs press into

the night, unaware of cold, impervious to darkness,

even the old blind one, which ventures deep

enough to disappear into the night. The colors

of the night are black for night and white

for anything that we can see within it. In

daylight, green dominates and everything

grows into its size. What is small yet infinite

at night is large yet finite during the day. Plants

surround us, prepared to conquer the world.

Maybe not in Arizona, though, which is

a different world created out of different

colors and substances. You have the same night

we have, but your day differs from ours, just

as we might share dreams but our lives differ. Lives,

as instances of daylight, always differ.

I wonder if words work the same way, if

the usual way we speak resembles

night, something that envelops us but

isn’t us. There are also the ways we use

words for ourselves, not so much

to communicate but to be, how you

visually twist a body of text until it is

something else, a contortionist of

words, a measure of your eye,

a means of not speaking, the way you

choose to not write, the stripping

of sense from every word, so that the

chitinous shell of the word remains,

empty but glistening and empty.

My mother-in-law continued to talk tonight

even after going to bed. She asked many times

what had made that last noise she had heard.

She said goodnight to the darkness, and repeated

that goodnight. She repeated the phrases she had

said many times during the day, phrases

that had lost their meaning except that they kept

her safe. The words meant nothing anymore,

but they protected her. If she had those words, if

she could only speak them, she knew she was safe.

This afternoon, I pulled out my inks,

a walnut ink of wavering browns and

India ink, which is always nothing but black,

and I drew letters and words with them,

but ones that didn’t exist, ones that existed

only as I willed them to be. While I worked,

spreading ink over pieces of white paper,

my mother-in-law kept asking me what

I was doing, and every time I said,

“I’m writing,” because writing is the process

of making words appear on a page, anything

we’ve made and seen can be a word to us.

It is too late for writing, too late for words.

Even this close to summer, the Adirondacks

hold their cold, and I need a warm sleep.

I should stop writing now, because I don’t have

the ability to write anymore, I cannot

write it right, and everything leans heavily

into sleep. I am reduced to a human weight. If I fall,

I could drown in the darkness surrounding us.

Comments

Post a Comment