40. raspberryblossoming

To pick a raspberry, we

fall to our knees, to give thanks,

to divulge praise to the moist earth beneath

dry earth, to sun, to intermittent

rain and bees that visit the temporary blossoms

of the thorny canes—to see, from below (human

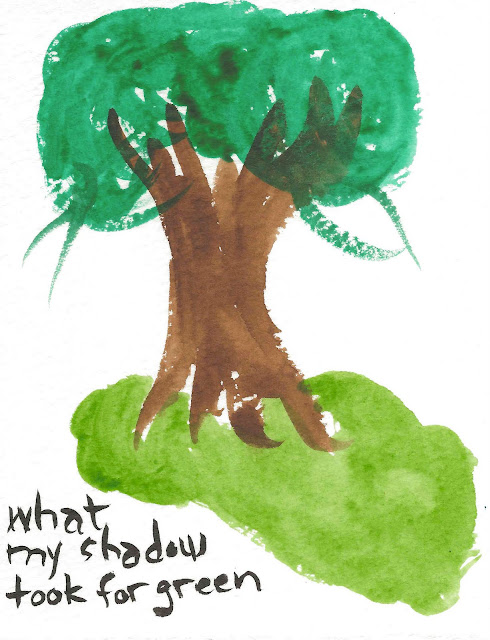

miniaturized by shade) the berries hidden by green

leaves in a canopy of storeys and shifting light, where

fruits of purpled black, red-purple, red, rose,

white or variegated in white and pink, with drupelets

rowed to remind of kernels on corn, evidence of summer,

when the fragments of nature divide themselves to

multiply into what we see as profusion, even though

not every berry is seen from an air of walking,

the least or greatest maybe slipping beneath

cover, the fruit reserved for neither bird

nor human, but earth, to mix with seed

and stick and leaves falling from an autumn lasting

until past the winter when seed cracks,

sprouts, sends up a beacon, message,

measure of a making without even promise

for harvest.

But it is all

nothing

but words.

You see

them and make them

seen. How a word is read because

a word is seen (not the sound of it

but), the form it takes for the eye. You

crack open the O to find the eye

within it. Every letter is a sculpture

that makes sense only through

dismantlement. You write, you work

with ink, you are a thinkink man.

Your pen is camera or pen, your

paper is paper, and you work the word

to find the word. You might cut

it back and use it

in a ntence. You might study

its sytructure, adding something

as you did. You might find

something beautrifulo in it,

because our language is

not simply aural. We speak in

a visual language, tongueless,

tongueless all the days, reading

the shapes and sounds of words

into our heads. Language as

the work of eyes

and hands,

earless, mouthless,

prone to

silence.

In these woods I’ve made myself to today,

fruits are small: twinberry’s red made silent

by profusion of its rounded green leaves, blueberry

bushes not as tall as a knee with fruit

smaller than a kernel of corn, and blackberry

in place of raspberry and those fruit still hard

and green and tiny as a drop of ink. Here

there is no harvest and just enough heat

to keep the woods growing (hemlock

beech, birch, oak). Here we don’t

have to drop to our knees

to find the fruit. This

is a place of the words

we hear, and a chorus of

bullfrogs, guttural, droning,

sing to us now, right

now, to let us know

that night, pure night,

lit by no lamp,

does not allow

for silent words.

In this dark place,

we use

our

ears.

fall to our knees, to give thanks,

to divulge praise to the moist earth beneath

dry earth, to sun, to intermittent

rain and bees that visit the temporary blossoms

of the thorny canes—to see, from below (human

miniaturized by shade) the berries hidden by green

leaves in a canopy of storeys and shifting light, where

fruits of purpled black, red-purple, red, rose,

white or variegated in white and pink, with drupelets

rowed to remind of kernels on corn, evidence of summer,

when the fragments of nature divide themselves to

multiply into what we see as profusion, even though

not every berry is seen from an air of walking,

the least or greatest maybe slipping beneath

cover, the fruit reserved for neither bird

nor human, but earth, to mix with seed

and stick and leaves falling from an autumn lasting

until past the winter when seed cracks,

sprouts, sends up a beacon, message,

measure of a making without even promise

for harvest.

But it is all

nothing

but words.

You see

them and make them

seen. How a word is read because

a word is seen (not the sound of it

but), the form it takes for the eye. You

crack open the O to find the eye

within it. Every letter is a sculpture

that makes sense only through

dismantlement. You write, you work

with ink, you are a thinkink man.

Your pen is camera or pen, your

paper is paper, and you work the word

to find the word. You might cut

it back and use it

in a ntence. You might study

its sytructure, adding something

as you did. You might find

something beautrifulo in it,

because our language is

not simply aural. We speak in

a visual language, tongueless,

tongueless all the days, reading

the shapes and sounds of words

into our heads. Language as

the work of eyes

and hands,

earless, mouthless,

prone to

silence.

In these woods I’ve made myself to today,

fruits are small: twinberry’s red made silent

by profusion of its rounded green leaves, blueberry

bushes not as tall as a knee with fruit

smaller than a kernel of corn, and blackberry

in place of raspberry and those fruit still hard

and green and tiny as a drop of ink. Here

there is no harvest and just enough heat

to keep the woods growing (hemlock

beech, birch, oak). Here we don’t

have to drop to our knees

to find the fruit. This

is a place of the words

we hear, and a chorus of

bullfrogs, guttural, droning,

sing to us now, right

now, to let us know

that night, pure night,

lit by no lamp,

does not allow

for silent words.

In this dark place,

we use

our

ears.

Comments

Post a Comment